Questões de Vestibular de Inglês

Foram encontradas 730 questões

Read Text to

answer question.

The article analyzes the relationship of Indigenous

Peoples with the public policy of Social Assistance (AS) in Brazil. Based on

data collected during field work carried out in 2014, will analyze the case of

the Indigenous Reserve of Dourados, Mato Grosso do Sul. In the first part, I

characterize the unequal relationship between society and national state with

Indigenous Peoples to, then approach the Welfare State politics as an

opportunity to face the violation of rights resulting from the colonial siege. Then

we will see if Dourados to illustrate the dilemmas and possibilities of

autonomy and indigenous role faced with this public policy. It is expected to

contribute to the discussion of statehood pointing concrete cases where the

local implementation of AS policy is permeable to a greater or lesser extent,

the demands of Indigenous Peoples by adaptation to their social organizations

and worldviews.

(BORGES, Júlio César. Brazilian society has made us poor: Social Assistance and ethnic autonomy of Indiggenous Peoples. The case of Dourados, Mato Grosso do Sul. Horiz. antropol. Disponível em: <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S0104-71832016000200303&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en>. Acesso em: 10 nov. 2018).

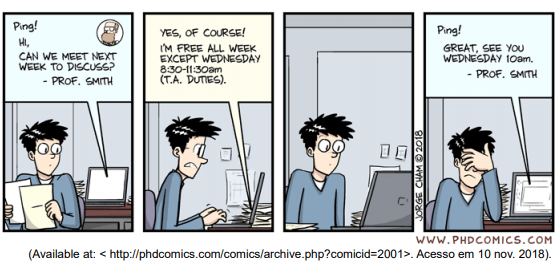

Read the comic to answer question.

According to the comic, it is correct to affirm that:

T E X T

Britain, Norway and the United States join forces with businesses to protect tropical forests.

Britain, Norway and the United States said Thursday they would join forces with some of the world’s biggest companies in an effort to rally more than $1 billion for countries that can show they are lowering emissions by protecting tropical forests. The goal is to make intact forests more economically valuable than they would be if the land were cleared for timber and agriculture.

The initiative comes as the world loses acre after acre of forests to feed global demand for soy, palm oil, timber and cattle. Those forests, from Brazil to Indonesia, are essential to limiting the linked crises of climate change and a global biodiversity collapse. They are also home to Indigenous and other forest communities. Amazon, Nestlé, Unilever, GlaxoSmithKline and Salesforce are among the companies promising money for the new initiative, known as the LEAF Coalition.

Last year, despite the global downturn triggered by the pandemic, tropical deforestation was up 12 percent from 2019, collectively wiping out an area about the size of Switzerland. That destruction released about twice as much carbon dioxide into the atmosphere as cars in the United States emit annually.

“The LEAF Coalition is a groundbreaking example of the scale and type of collaboration that is needed to fight the climate crisis and achieve net-zero emissions globally by 2050,” John Kerry, President Biden’s senior climate envoy, said in a statement. “Bringing together government and privatesector resources is a necessary step in supporting the large-scale efforts that must be mobilized to halt deforestation and begin to restore tropical and subtropical forests.”

An existing global effort called REDD+ has struggled to attract sufficient investment and gotten mired in bureaucratic slowdowns. This initiative builds on it, bringing private capital to the table at the country or state level. Until now, companies have invested in forests more informally, sometimes supporting questionable projects that prompted accusations of corruption and “greenwashing,” when a company or brand portrays itself as an environmental steward but its true actions don’t support the claim.

The new initiative will use satellite imagery to verify results across wide areas to guard against those problems. Monitoring entire jurisdictions would, in theory, prevent governments from saving forestland in one place only to let it be cut down elsewhere.

Under the plan, countries, states or provinces with tropical forests would commit to reducing deforestation and degradation. Each year or two, they would submit their results, calculating the number of tons of carbon dioxide reduced by their efforts. An independent monitor would verify their claims using satellite images and other measures. Companies and governments would contribute to a pool of money that would pay the national or regional government at least $10 per ton of reduced carbon dioxide.

Companies will not be allowed to participate unless they have a scientifically sound plan to reach net zero emissions, according to Nigel Purvis, the chief executive of Climate Advisers, a group affiliated with the initiative. “Their number one obligation to the world from a climate standpoint is to reduce their own emissions across their supply chains, across their products, everything,” Mr. Purvis said. He also emphasized that the coalition’s plans would respect the rights of Indigenous and forest communities.

From: www.nytimes.com/April 22, 2021

T E X T

Britain, Norway and the United States join forces with businesses to protect tropical forests.

Britain, Norway and the United States said Thursday they would join forces with some of the world’s biggest companies in an effort to rally more than $1 billion for countries that can show they are lowering emissions by protecting tropical forests. The goal is to make intact forests more economically valuable than they would be if the land were cleared for timber and agriculture.

The initiative comes as the world loses acre after acre of forests to feed global demand for soy, palm oil, timber and cattle. Those forests, from Brazil to Indonesia, are essential to limiting the linked crises of climate change and a global biodiversity collapse. They are also home to Indigenous and other forest communities. Amazon, Nestlé, Unilever, GlaxoSmithKline and Salesforce are among the companies promising money for the new initiative, known as the LEAF Coalition.

Last year, despite the global downturn triggered by the pandemic, tropical deforestation was up 12 percent from 2019, collectively wiping out an area about the size of Switzerland. That destruction released about twice as much carbon dioxide into the atmosphere as cars in the United States emit annually.

“The LEAF Coalition is a groundbreaking example of the scale and type of collaboration that is needed to fight the climate crisis and achieve net-zero emissions globally by 2050,” John Kerry, President Biden’s senior climate envoy, said in a statement. “Bringing together government and privatesector resources is a necessary step in supporting the large-scale efforts that must be mobilized to halt deforestation and begin to restore tropical and subtropical forests.”

An existing global effort called REDD+ has struggled to attract sufficient investment and gotten mired in bureaucratic slowdowns. This initiative builds on it, bringing private capital to the table at the country or state level. Until now, companies have invested in forests more informally, sometimes supporting questionable projects that prompted accusations of corruption and “greenwashing,” when a company or brand portrays itself as an environmental steward but its true actions don’t support the claim.

The new initiative will use satellite imagery to verify results across wide areas to guard against those problems. Monitoring entire jurisdictions would, in theory, prevent governments from saving forestland in one place only to let it be cut down elsewhere.

Under the plan, countries, states or provinces with tropical forests would commit to reducing deforestation and degradation. Each year or two, they would submit their results, calculating the number of tons of carbon dioxide reduced by their efforts. An independent monitor would verify their claims using satellite images and other measures. Companies and governments would contribute to a pool of money that would pay the national or regional government at least $10 per ton of reduced carbon dioxide.

Companies will not be allowed to participate unless they have a scientifically sound plan to reach net zero emissions, according to Nigel Purvis, the chief executive of Climate Advisers, a group affiliated with the initiative. “Their number one obligation to the world from a climate standpoint is to reduce their own emissions across their supply chains, across their products, everything,” Mr. Purvis said. He also emphasized that the coalition’s plans would respect the rights of Indigenous and forest communities.

From: www.nytimes.com/April 22, 2021

T E X T

Britain, Norway and the United States join forces with businesses to protect tropical forests.

Britain, Norway and the United States said Thursday they would join forces with some of the world’s biggest companies in an effort to rally more than $1 billion for countries that can show they are lowering emissions by protecting tropical forests. The goal is to make intact forests more economically valuable than they would be if the land were cleared for timber and agriculture.

The initiative comes as the world loses acre after acre of forests to feed global demand for soy, palm oil, timber and cattle. Those forests, from Brazil to Indonesia, are essential to limiting the linked crises of climate change and a global biodiversity collapse. They are also home to Indigenous and other forest communities. Amazon, Nestlé, Unilever, GlaxoSmithKline and Salesforce are among the companies promising money for the new initiative, known as the LEAF Coalition.

Last year, despite the global downturn triggered by the pandemic, tropical deforestation was up 12 percent from 2019, collectively wiping out an area about the size of Switzerland. That destruction released about twice as much carbon dioxide into the atmosphere as cars in the United States emit annually.

“The LEAF Coalition is a groundbreaking example of the scale and type of collaboration that is needed to fight the climate crisis and achieve net-zero emissions globally by 2050,” John Kerry, President Biden’s senior climate envoy, said in a statement. “Bringing together government and privatesector resources is a necessary step in supporting the large-scale efforts that must be mobilized to halt deforestation and begin to restore tropical and subtropical forests.”

An existing global effort called REDD+ has struggled to attract sufficient investment and gotten mired in bureaucratic slowdowns. This initiative builds on it, bringing private capital to the table at the country or state level. Until now, companies have invested in forests more informally, sometimes supporting questionable projects that prompted accusations of corruption and “greenwashing,” when a company or brand portrays itself as an environmental steward but its true actions don’t support the claim.

The new initiative will use satellite imagery to verify results across wide areas to guard against those problems. Monitoring entire jurisdictions would, in theory, prevent governments from saving forestland in one place only to let it be cut down elsewhere.

Under the plan, countries, states or provinces with tropical forests would commit to reducing deforestation and degradation. Each year or two, they would submit their results, calculating the number of tons of carbon dioxide reduced by their efforts. An independent monitor would verify their claims using satellite images and other measures. Companies and governments would contribute to a pool of money that would pay the national or regional government at least $10 per ton of reduced carbon dioxide.

Companies will not be allowed to participate unless they have a scientifically sound plan to reach net zero emissions, according to Nigel Purvis, the chief executive of Climate Advisers, a group affiliated with the initiative. “Their number one obligation to the world from a climate standpoint is to reduce their own emissions across their supply chains, across their products, everything,” Mr. Purvis said. He also emphasized that the coalition’s plans would respect the rights of Indigenous and forest communities.

From: www.nytimes.com/April 22, 2021

T E X T

Britain, Norway and the United States join forces with businesses to protect tropical forests.

Britain, Norway and the United States said Thursday they would join forces with some of the world’s biggest companies in an effort to rally more than $1 billion for countries that can show they are lowering emissions by protecting tropical forests. The goal is to make intact forests more economically valuable than they would be if the land were cleared for timber and agriculture.

The initiative comes as the world loses acre after acre of forests to feed global demand for soy, palm oil, timber and cattle. Those forests, from Brazil to Indonesia, are essential to limiting the linked crises of climate change and a global biodiversity collapse. They are also home to Indigenous and other forest communities. Amazon, Nestlé, Unilever, GlaxoSmithKline and Salesforce are among the companies promising money for the new initiative, known as the LEAF Coalition.

Last year, despite the global downturn triggered by the pandemic, tropical deforestation was up 12 percent from 2019, collectively wiping out an area about the size of Switzerland. That destruction released about twice as much carbon dioxide into the atmosphere as cars in the United States emit annually.

“The LEAF Coalition is a groundbreaking example of the scale and type of collaboration that is needed to fight the climate crisis and achieve net-zero emissions globally by 2050,” John Kerry, President Biden’s senior climate envoy, said in a statement. “Bringing together government and privatesector resources is a necessary step in supporting the large-scale efforts that must be mobilized to halt deforestation and begin to restore tropical and subtropical forests.”

An existing global effort called REDD+ has struggled to attract sufficient investment and gotten mired in bureaucratic slowdowns. This initiative builds on it, bringing private capital to the table at the country or state level. Until now, companies have invested in forests more informally, sometimes supporting questionable projects that prompted accusations of corruption and “greenwashing,” when a company or brand portrays itself as an environmental steward but its true actions don’t support the claim.

The new initiative will use satellite imagery to verify results across wide areas to guard against those problems. Monitoring entire jurisdictions would, in theory, prevent governments from saving forestland in one place only to let it be cut down elsewhere.

Under the plan, countries, states or provinces with tropical forests would commit to reducing deforestation and degradation. Each year or two, they would submit their results, calculating the number of tons of carbon dioxide reduced by their efforts. An independent monitor would verify their claims using satellite images and other measures. Companies and governments would contribute to a pool of money that would pay the national or regional government at least $10 per ton of reduced carbon dioxide.

Companies will not be allowed to participate unless they have a scientifically sound plan to reach net zero emissions, according to Nigel Purvis, the chief executive of Climate Advisers, a group affiliated with the initiative. “Their number one obligation to the world from a climate standpoint is to reduce their own emissions across their supply chains, across their products, everything,” Mr. Purvis said. He also emphasized that the coalition’s plans would respect the rights of Indigenous and forest communities.

From: www.nytimes.com/April 22, 2021